While global outrage has been raised on concerns of electoral fraud and digital manipulation in North America, more emerging markets are often left out of the conversation. The shape of the web bends, deepens, and constricts itself to destroy the most vulnerable. This is the Punishing of Philippines.

The Testing Grounds

Entering the Extremism of the Online World

Nations like India and the Philippines have long served as testing grounds for big technology. In the wake of insecurity, cyberwarfare, and immense adoption of online platforms with little digital literacy to back it, we are witnessing the unprecedented rise of the extremist web. Violent rhetoric and hatred have gone mainstream, and it’s likely that the next manifesto behind an act of terror goes on the internet first. How has the web been architected to allow for this potential in these regions? While left out of the conversation, they provide us important studies and warning signs about how internet connectivity does not inherently equate to progress.

An unprecedented time and age for innovation and access to the internet has in parallel, also opened up opportunities for this medium to be exploited. Altering public discourse, spreading disinformation, and radicalizing the reader in front of the screen. How does the infrastructure of the web leave these nations susceptible to digital radicalism? What rabbit holes are left on their local internet’s infrastructure that allow this destabilization in the first place, and what are the general implications of these networks in the third-world?

The intertanglement of poor technological infrastructure, state subservience to disinformation tactics to manipulate the public, and an oversaturation of internet technologies with insufficient digital literacy training bring developing nations to witness a new level of exploitation. The Philippines confronts a punishing, and the consequences that come with it to its democracy.

Before understanding the punishing, we must first look into the landscape that has enabled this act to occur in this first place. Take a look at the web in the realm of the Philippines.

The Shape of the Internet

What does the web look like?

In one of the most online and digital nations in the world, we witness the malleable, intangible idea of the web shaped without our input before being forced into our hands. How has the technological infrastructure abandoned developing nations in the name of progress, and how much can we blame the makers and the way they have enforced their adoption?

Boris Beaude views the internet as a space for “synchrorisation” at a worldwide scale. Where synchronization refers to a shared experience in time, synchrorisation is a common space (Druhle, 2016). As it stands, the internet is the only space that we share globally. Distance in the internet is near-irrelevant as we are all physically bound to another area by virtually a single click, yet space weighs itself heavily. In practice, our search engines, social media feeds, and platforms that index, aggregate and present the spaces of the web to us provide us viewers the architecture of the web that we interact with today. Man-made machines and browsers decide the relationships we have with the mass of content on the internet.

In 1960, J.C.R. Licklider envisions what symbiotic relationships between man and computer could look like using similar notions of time and motion. In his dream of man-computer symbiosis, the human brain pairs with the computational power of computers, where thought from man evolves and expands with support from the computer. Where our interactions with the internet now are gated, a more complementary relationship would require certain prerequisites. Amongst which Licklider presents the issue of a speed mismatch between men and computers’ processing thought. Large-scale computers are too fast, costly, and can’t realistically compute with men; the brain can perform about a thousand basic operations per second, 10 million times slower than the computer. Of course, even high-processing computers with distribute data systems struggle at human tasks: reading handwritten letters, navigating ambiguous tasks, and of course, emotional expression.

Licklider and Beaude both note a distinct divide in the realm of digital space and processing that can both be solved by human intervention. In the making of digital gateways like browsers and search engines, information is only gated and made accessible by human program and design. The browser to the ease of accessing even deeply gated websites, the search engine to the algorithm dictated by the programmer. Despite Google’s 90% market share dominance in search, new platforms are challenging their lead. DuckDuckGo sells itself as offering real privacy, no search tracking, and no user history searching; every search term and query receives results identical to what another user on the engine would type. Meanwhile, Google as a behemoth has over a thousand engineers working on their core search products. This still excludes the thousands more across design, marketing, product, operations, and beyond that cascade decisions that affect the base browsing experience for the billions of searches that are queried every single day.

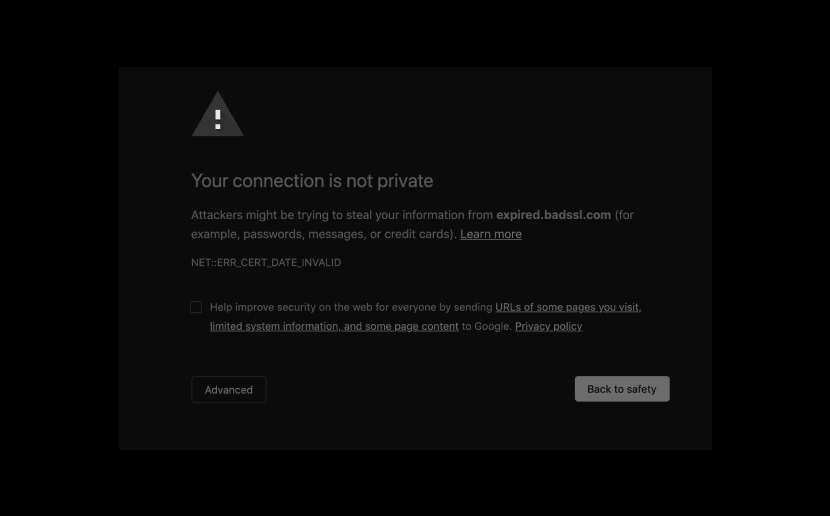

Warning Signs

Google Chrome warns you––or even entirely blocks you––from sites with misleading security certificates. The Tor browser redirects internet traffic entirely for anonymity, where user movements and usage are near-untraceable; Onion routing is another layer of encryption (referred to as the “dark web”) accessible only through proxy software such as Tor under the “.onion” top level domain.

Man himself gates the web, dictating how the flow of information through space. Corporations behind the most frequently used technologies, from search engines to browsers, controlling how the masses interact. While the early web was relatively decentralized, internet activity is heavily concentrated in specific nodes of the web run by the Googles and Amazons of the web. Further complicating our interactions with it, the web’s development is largely dictated by the United States. Despite being a global experience, cloud computing services, the headquarters of these giants themselves, and even the distribution of domain names are governed by bodies headquartered in the United States.

Taking a step back, what if people don’t even understand that they’re on the internet?

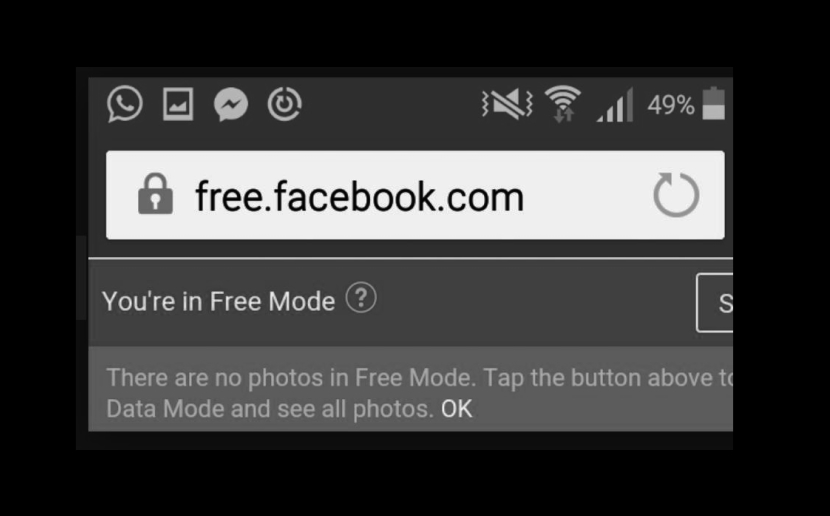

Social media giants like Facebook and YouTube design stripped-down versions of their platforms to operate in regions with weaker infrastructural support across India, Africa, and Southeast Asia. Android-friendly Facebook Lite minimizes data and processing-intensive features like videos and location services, showcasing only low-resolution image thumbnails, text, and messaging to adapt better to the pervasiveness of 4th-generation mobile connections and internet cafes as main connectivity sources. In these emerging markets, smartphones are more commonly owned; 53% of mobile device owners in the Philippines have smartphones as opposed to 23% with basic phones (Pew Research Center, 2020). Smartphones become a gateway to connection, information, and entertainment. This is elevated further in the Philippines, with the population spending an average of about 10 hours a day on the internet, the highest in the world according to a Hootsuite report; social media penetration also stands at 71%––with over 80 million Filipinos exploring the web (CNN Philippines, 2019).

The World of "Free" Internet

The Internet As Facebook

But even groups like Filipinos don’t understand that they’re on the internet. Frequenting the internet on gated platforms, users today may immerse themselves in platforms... and never escape it. They report that they’re using social media and networks like Facebook and YouTube, but they don’t report that they’re on ‘the internet’.

Studying a similar gap with internet usage in Thailand and Indonesia, Rohan Samarijiva writes that “it seemed that in their minds, the Internet did not exist; only Facebook”.

"It seemed that in their minds, the Internet did not exist; only Facebook.”

Looking into engagement ratings in a voter registration campaign I had managed in 2019. Iboto.ph, a voter education campaign run on Facebook to funnel users to the website where they could access more information about candidates received a peak of three million engagements in May 15th, 2019, during the votecount after the 13th’s midterm elections. 93% of interactions restricted users to Facebook-only content, sharing, commenting, or clicking links to related pages and electoral candidate materials that were also on Facebook. Only 7% of interactions brought users to outbound platforms. During usability testing sessions, it was found that most viewer devices were on Android mobile devices, reliant on Facebook Lite or may have been on it for purposes of conserving data (Amisola, 2019).

“Free Facebook” began as an experiment in 2013 through a partnership with the product company and telecommunication giant Smart. The partnership would provide users free mobile Internet services without any data charges at all (in a country where data is faster and more accessible than wi-fi), addressing the internet access gap faced then by 38% of the population (Pagulong & Desidero, 2015). On paper, the company offers a curated list of services (not simply restricted to Facebook) to sites like BBC News, ESPN, and Bing. While for instance, users can view Bing search results, tapping in to access any page beyond walls the user with a prompt to purchase data. Further, no email providers are provided.

While public perception and trust in social media platforms has fallen with electoral breaches in North America, the same is difficult to be said for users in the developing world who have it as their only resource and gateway.

The Internet Today

Architecturally, our web gravitates towards centralized operators such as Facebook, Google, and Microsoft. Majority of experiences that one has on the internet take place with these corporations. In 2013, Google made up 25% of American internet activity, a quarter of it; seven years before, it had only represented 6% of traffic (Boyette, 2013). The control that these large operators hold in emerging markets is even more prominent. Of the 69 million Filipinos that have access to the internet, nearly 100% have a Facebook account (Swearingen, 2018). “[The] Free Facebook program has become so successful that it’s hard to imagine how Facebook and the Philippines could ever untwine themselves from each other,” Swearingen writes. From voter campaigns to mass disinformation and manipulation, one platform feeds the central discourse of the Philippines.

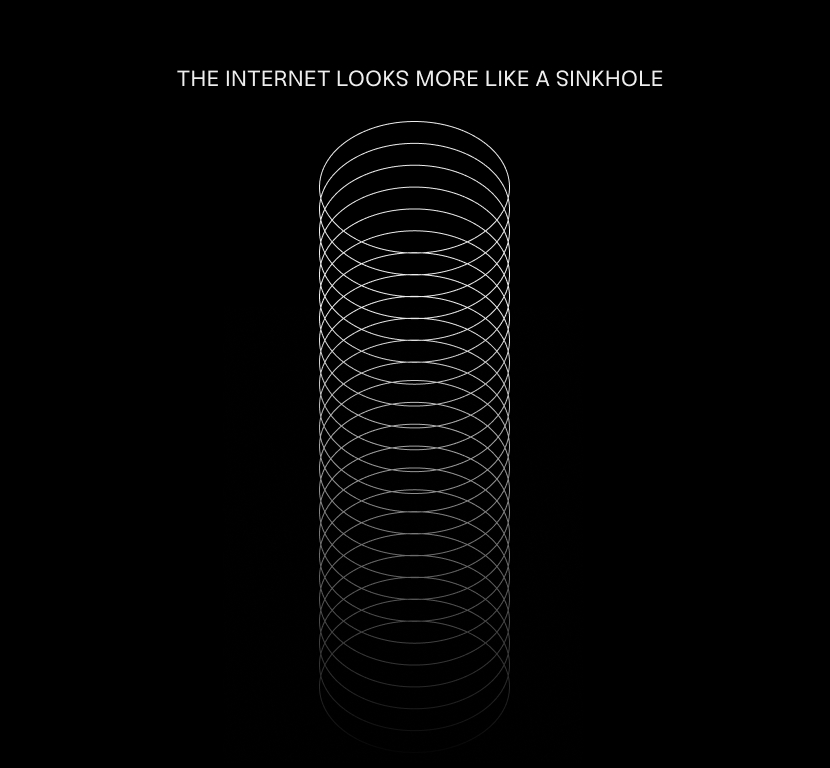

As opposed to a decentralized internet, the tactics deployed by these companies effectively architect the internet into deep, centered holes. Centralized social media sites generate dependence on their platforms, ignoring fundamental issues in access through faux-good will in subsidizing activity that only benefits them in the long-term. In the meantime, digital literacy, energy, and education continue to be abandoned. They are completely barred and in effect, lead "their services to be the whole internet that people know.

Our web looks more like a sinkhole. Its depth swallows in users who are consuming it more actively and aggressively than ever before, having users wander around internal link after internal link––creating irreplaceable feedback loops.

The issue of free information is not a technological one, but an economic one. Access to most content on the internet are theoretically divided by a single click. Nathan Robinson writes about how universal access is a harrowing thing because it takes away from the issue of ownership (Robinson, 2020). Facebook is incentivized to subsidize a tightly-curated web for their own activation rates and the data binded to every user who explores the small web that Facebook had carved out. Even free systems of distribution like the American public library system carved out spatial limitations to areas that should not be gated at all: online library limits where PDFs read through browser readers cap at three “borrowers” despite everything living online need to exist in publishers’ eyes. The Philippines however, has no systems like this. The government website to know about the nearest library, if your locality has a public library at all, is gated behind Facebook’s wall as well.

Our web now remains a series of abysses, loosely connected, serving neither man or machine.

Instead of a symbiotic relationship with man and machine, man has gated behind himself even a fragment of the potential of the web. Where Licklider preconditioned architecture, speed, and memory that synchronised with one another and Beaude dreamed of synchrorisation of the internet, the web deployed in the name of free and equitable access in the emerging world fails. Our web now remains a series of abysses, loosely connected, serving neither man or machine.

Extremism in SEA

The Radicalization of

Southeast Asia

Extremist behaviors here are defined as those “encouraging, condoning, justifying, or supporting the commission of a violent or harmful act to achieve political, ideological, religious, social, or economic goals.” The design of the centralized web makes it easier for man to follow singular modes of thought, as singular platforms, services, and algorithms manipulate the consumption of the everyday viewer. We have tapped into an interface that catalyzes dangerous and malignant thought in the passive viewer, causing them to adopt––and potentially enforce––harmful beliefs onto others.

The content and regulation of the internet is centered around the United States, along with the dispatch of so-called free internet services for equal access. Unbeknownst to many policymakers, regulators, and technologists that govern these concentrations of the internet used by the global space, they face severe physical and environmental limitations that may not be addressed by sole subsidy and manipulation at all. Many of these countries have yet to adopt digital literacy education, adequate telecommunications and energy networks, public research institutions, or established media bureaus and organizations. Fundamentally, the lack of education, energy, and health already leaves these populations and their youth susceptible to influence and manipulation to extremist behaviors. The web merely acts as another accelerator to violent belief. Extremism online can occur in intentional acts of deception to even casual behavior: politicians shifting the Overton window and gaslighting their constituents on backfired promises, domestic terror groups and anonymous forums recruiting visitors to their activities, or your newsfeed simply favoring violent, extremist content shown to you without warning to the point of desensitization.

The region, as a testing grounds for new technologies, is left with all the consequences of challenges met and abandoned, and challenges yet to be solved from the West.

Over the past decade, we’ve seen the landscape of the web in emerging markets change fundamentally with this recognition. The region, as a testing grounds for new technologies, is left with all the consequences of challenges met and abandoned, and challenges yet to be solved from the west.

The Making of the Facebook Radical

Extremism Emerging

The online rabbit holes of the internet set up the perfect stage for extremism to be deployed. Inherently, platforms like Facebook’s ‘Free Basics’ set it up so that material can be unquestionably disseminated and shared. Posts travel through circles and break through feeds in bursts, gathering in benediction through the form of reactions and comments.

When larger influencers and figures post content, their share of the internet sinkhole broadens, and the weight of their influence draws deeper holes. Their platform becomes a facilitator and chamber for their thoughts. Easily, one could game the system by gaming the algorithm. Posting content that elicits more reactions that then gets shown to more people’s feeds, spreading their choice of ideology farther with little room for backlash.

While tense social and political climates in traditional spaces do no favors against the growing radicalization of young people, the architecture and infrastructure of the internet further stress the severity of this extremism.

In the beginning of the 2000s, beheading videos became a distinct tactic for terrorist groups. The method of execution itself is ancient, but the act is violent, obscene, and classically gruesomely shocking. Then-Bureau Chief of The Wall Street Journal, Daniel Pearl had been kidnapped and killed by Al-Qaeda in 2002 before being beheaded by his captors. The disturbing video of his death was of unnerving quality and scripted with Pearl denouncing his own identity. Anonymously uploaded and spread, the video ends with his hostage-takers making demands and threatening to repeat this beheading “again and again. Anonymous forums, shock sites, then second-handed news sites circulate these videos and draw growing fear from the general populace. It’s not rare for social media sites to host beheading videos, either (Kelion, 2013).

While Pearl’s death wasn’t not strictly proliferated on social sites (Facebook was founded years after 2002), there was an undeniable wave of copycat snuffpieces and a genuine potential in abusing the web. The introduction of social media sites then fit perfectly: they were the best place to stir fear, share discussion, and potentially desensitize the public. While shock videos in the early 2000s would be picked up by media outlets and television with carefully scripted commentary, social media would leave them unchecked and free to comment on, meeting potentially more feedback than just the societal norm of abhorrence and condemnation.

The same tactics are growing unchecked on social media. In 2017, an armed conflict in the Philippines’ Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) stretched five months and led to over a thousand casualtiesm. The city of Marawi was sieged as a result of a long struggle with domestic terrorism between the state and Maute Group fighters known as the Abu Sayaff (also linked to Al-Qaeda) with objective to institute an Islamic caliphate in the island of Mindanao. The extremist group took advantage of the predominant Muslim population in the region amidst a majority Roman Catholic nation, record-high poverty levels, and high out of school youth rates that contributed to key factors in their engagement: poverty and kinship (The Asia Foundation, 2018).

In plain sight, designated members of terrorist groups promoted terrorist activity. On public Facebook profiles, they post tight-knit group shots bearing flags symbolic of terrorism with over 109 reactions. Facebook Pages and Groups around Maguindanao and Bangsomoro post provocative content and screenshots, stoking outrage from young Moros in their mother tongue. These easily slip behind Facebook’s already scrutinized surveillance: to machine vision, photos of militant garb and ammunition look indistinguishable to generic photos of soldiers that would be considered patriotic, language barriers slip past content censors fine tuned for English, and content moderators have little signal to individual pieces of media that don’t raise any flags. Recruiting is also done casually and slowly: comments on provocative and popular posts, private messages, and contained conversation in local-interest Facebook groups. Recruitment also focuses on a friends-of-friends basis; it’s hard to say no to mutuals, and as Abu Sayaff influence increased, so did their recruitment pool. Even if an individual isn’t outright recruited to join the guerilla militant group, they spread their rhetoric to thousands of others as they begin to rethink the side of terror.

During the five-month siege, extremists would post acts of violence and destruction as they occupied Marawi. Hundreds of thousands of Filipinos were displaced in the midst of government airstrikes, warfare, and the looting of thousands of homes. Then in my senior year of high school, I would open my phone and see a video reposted for the seventh time around, originally from one of countless Abu Sayaff groups entering Catholic churches to point guns and scream at civilians before shattering religious statues, setting the room ablaze. These videos would be neatly fed to me by the Facebook newsfeed in between class announcements and lighthearted shares from friends. These materials weren’t only shaky phone videos and incomprehensible attacks; they were also drone shots of destruction, individual messages from captives with captions (much like the Daniel Pearl video), and photos reinstating their message and mission. It wasn’t outlandish to see messages of support directed at them.

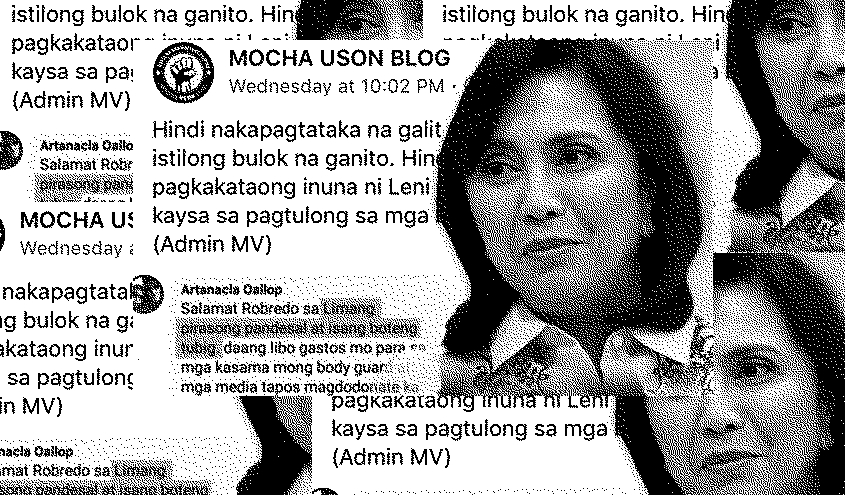

The case of domestic terror group Abu Sayaff’s manipulation isn’t a lone one. In the Philippines, state authorities themselves act as figures of spectacle, dominating public conversation as they sway the masses’ opinion on media, freedom, and human rights in cruel acts of deceit and despotism. A country already notorious for attacks on journalists with a threatened state of press freedom, large media publications have constantly been targeted by the government for their critical reporting. Salvador Panelo, spokesperson and chief legal counsel for President Rodrigo Duterte, publicly denounces online publications like Rappler as he imbues images of their virulence in spreading false news against the President––claiming their reporting is an attempt at destroying the government (Hammer, 2019). Journalist and Editor-in-Chief of Rappler Maria Ressa is then subsequently arrested for cyberlibel thanks to state-sponsored accusations, and in 2020, found guilty of cyberlibel. These patterns of politically-motivated arrests and threats spread rampant on social media without sign of relent, even against the Vice President. Post-Typhoon Ulysses that had devastated the nation in November 2020, Panelo publishly lashes out at a photo posted by the Office of the Vice President of a shot of relief operations, claiming her to be taking credit for government-funded relief efforts on her own. After learning that the pictured relief operations were entirely managed by her own office, he half-heartedly apologized claiming that he was “not apologizing for distributing or peddling a false info [sic]”. With disaster response in emerging markets often becoming a game of philanthropy and saviorism, remarks like Panelo’s quickly-circulating on social media shapes public perception with little rebound room to retract and correct error when algorithmically, allegations go favored. In a Facebook post on that same day, Vice President Robredo writes that “it is just so unfortunate that government officials like Sec Panelo have become fake news peddlers themselves.”

In emerging markets, there is no need for unmoderated and virulent 4chans to awaken hatred. In fact, it wouldn't be efficient.

In emerging markets, there is no need for unmoderated and virulent 4chans to awaken hatred. In fact, it wouldn't be efficient. There is already a machine in the form of the gated internet that can fuel the chaos of the web. 8chan's founders themselves lived with Filipina wives somewhere around the Philippine capital for years, where Gamergate, QAnon, Trumpism, and mass shootings slipped under the rug. (It was only in February 2020 that an arrest warrant was issued for Fredrick Brennan under the Philippines' cyberlibel law; 8chan was founded in 2014.)

In the name of Google's goal of making information universal, information is handpicked to what the few deem useful for the masses to know. In the name of connectivity and closeness, we have descents into disinformation and content rabbit holes that turn relationships into metrics, extremes as a regularity. The web carved out for the Philippines is in its own, a punitive machine for all who dwell on it. Beyond moderation and algorithms, we are left to entrust the some-100 million individuals in the country to pick from a narrowed-down selection of half-truths. What alternate reality can humans believe when this is the entire information sphere they're presented with?

The potential for exploitation here becomes exponentially magnified: not only do platforms like Facebook become the Internet itself, Facebook becomes all the Information that people know.

The sink holes of the web favor information meant to divide and polarize, with false claims and attacks left to circulate across media publications and journalists long-attacked and distrusted by the public. Filipinos here are largely left to fend for themselves. Where the West at the very least has Twitter take reactionary measures to safeguard against false claims by President Trump, the Philippines has state actors and disinformation networks manipulating the flow of information. The potential for exploitation here becomes exponentially magnified: not only do platforms like Facebook become the Internet itself, Facebook becomes all the Information that people know.

We now live in a web that has enacted an imperialistic grasp on humanity. However here, we are governed by people with little understanding or respect for their own influence or maliciously abuse their power. Not only do we have the grand leaders to blame, we now have to deal with consequences from the bottom-up as more and more pawns realize the potential of the web in seeding malignant thought that then infiltrates a greater cultural hegemony.

Political tact is synonymous with social media manipulation. Algorithm or not, we are bound to tread around hate. The manifesto is laid out on anonymous forums or on Facebook feeds in broad daylight. Push and pull towards terror happens through friend requests, and even encryption won't save us. Every transaction made in the name of openness further conquers our communications for nefarious purposes, and this is bound to be celebrated in the name of unquestioned connection.

Interactive

The Rabbit Holes of the Web

Not all posts showcased in the journey remain publicly available, and for purposes of the interactive, have been recreated to showcase the materials.